The main thesis of the essay is that the Run and Shoot Offense, particularly at the NFL level, was unfairly maligned by casual fans and lazy reporters, and remains a devastating scheme that should be given another chance. Mellor backs this argument up with convincing enough logic and facts, but near the end of the article he answers his own question of why the Run and Shoot died out: it didn't. Its principles have been incorporated, Borg-like, into every NFL offense today. Like the timing routes of the West Coast Offense or the zone run game of Alex Gibbs and the Redskins, once the effectiveness of the Run and Shoot's self-adapting routes had been demonstrated, every team in the league copied them. No NFL team runs the "pure" Run and Shoot offense of Mouse Davis anymore, and even June Jones, now head coach at SMU, has adapted his offense to base out of the shotgun and use less motion than he used as a player at Portland State or as the coach of the Falcons. But remnants of the scheme certainly live on in almost any modern passing offense, and the "pure" offense still has a dedicated following as a High School offense.

There is one explanation for the demise of the Run and Shoot hidden in the article that stands out to me (and it's not the zone blitz, whose rise around the time of the R&S' decline was probably more coincidental than anything). The NFL of the late 1980's and early 1990's was much less balanced than it is today. In High School or NCAA football, there is an incentive to try an inventive scheme if you can't possibly compete with the dominant teams on their terms, and so it was in NFL at one time. Now that parity is the norm at the game's highest level, the marginal benefit of succeeding with something innovative doesn't compensate as well as it once did for the risk of the coach being blamed (rather than the players) for failure.

If you are interested in learning more about the Run and Shoot (Mouse Davis version), Al Black's excellent Coaching Run and Shoot Football is a great reference for the offense used at the University of Houston and elsewhere, along with Coach Black's addition of a dive-option running game to add another dimension to the attack. For information on the original Run and Shoot offense invented by Tiger Ellison, the best source is the book Ellison himself wrote in 1965, Run-and-Shoot Football: Offense of the Future (reprinted in 1985 as Run-and-Shoot Football: The Now Attack).

Anyway, without further ado...

RESTART THE REVOLUTION

BY JOSEPH MELLOR

A History and Overview of the Run and Shoot Offense

"It is one thing to jump onto a moving train. It is another to stop a train and turn it around."-Gary Barnett, Head Coach Northwestern University

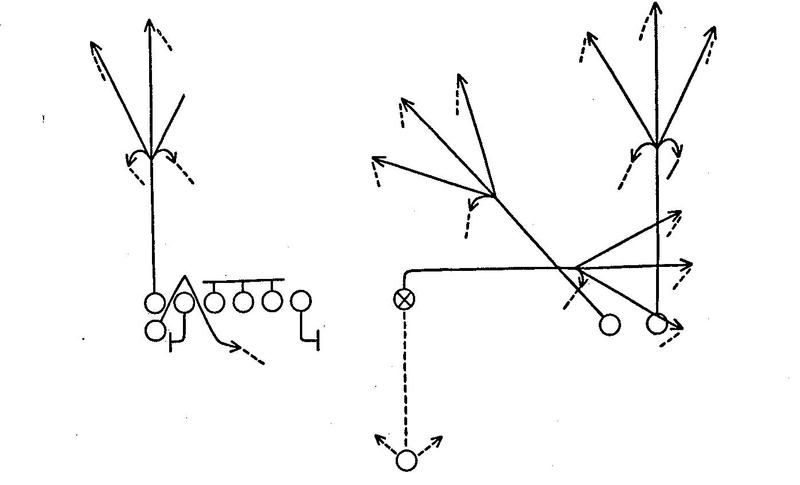

In 1958, Glenn Ellison, a high school football coach from just outside Columbus, Ohio was 0-4-1. One day, as he drove home from work, he stopped by at a park and observed some youngsters playing a game of pick-up football. Ellison watched eagerly as a slender passer with a weak arm ran around throwing passes to his friends who simply ran away from the defenders. Ellison was mesmerized. From this night at the park he came to two grand conclusions; it is more natural to throw on the run, and it is more effective to allow a player to react to what he sees instead of just giving him a pass route and hoping he's good enough to accomplish it. From there a monster was born. The next day he drew up a formation he called the Lonesome Polecat, which, as he puts it, he would never use for a whole season and calls its full time use a "departure into insanity." The offense put seven offensive players on one side of the field, with the quarterback and center in the middle of the field, and two lonesome players to the right side of the field:

On the snap of the ball, no one, including the players themselves, knew what was going to happen. They simply had the quarterback run to one side and each receiver, after five steps, run to an open area using a simple set of rules:"

"He right, I left!

"He left, I right!

"He come, I go!

"He go, I stay!"

A traditional offense of that time kept both their ends tight to the tackles and their slots were generally in the backfield. The name Ellison dubbed his creation was "Run and Shoot" because he modeled his offense after basketball, which has a point guard running around throwing to players that "get open" by running to open areas. While the Run and Shoot left many of the Polecat ideas behind, it took the thinking of reading defenses to determine what action to take. Only this time, it was usually one defender who would determine the course of execution. To do this Ellison became one of the first to number defensive personnel and base his teams' actions on the reactions of a specific defender.

Ed. Note: In the Run and Shoot, the passer's reads are often based on the movement of the #4 defender, who is nominally the flat defender. Disguising the defensive players' roles both before and after the snap to confuse this read is therefore key to defending this offense. It's a dangerous game, however, since a poor rotation can turn out worse than none at all.

Although the Run and Shoot was a child of the Lonesome Polecat, as Ellison puts it, "The offspring far out surpassed the parent as a means for scoring touchdowns." His offense would go on to average one touchdown every ten plays (five touchdowns per game) for the next four years. During this time Ellison's teams were 38-7 and three of his quarterbacks made the all state football team. The offense scored as many as 98 points in a single game.

Darrel "Mouse" Davis, a contemporary of Ellison's in Milwaukie, Oregon, took this idea along with the formation and tied up the loose ends. Mouse de-emphasized the running game, and put together a package of 3 running plays and five passing plays that today constitute the current Run and Shoot package. Modern day Run and Shoot theory was contingent on a few very basic principles. First, the Run and Shoot must be able to recognize how it is being defended. In Ellison's theory, he mapped out basic components of how a defense may combat his package, but his rules were applied to one defender. Davis categorized coverages into four different groups (three deep zone, two deep zone, man-to-man, and Blitz) of how an entire defense would play him, and instilled variations of his five plays for each coverage. So in fact, his five plays were really at least twenty, and many had several options for receivers to take advantage of. The result is that no matter what the defense chooses to do, the receivers will "run where they ain't." This idea in itself is controversial, as some claim that it makes the game complicated for players, and gives them too much freedom. However, Super Bowl Coach Tom Flores, in his critique of the Run and Shoot counters that, "This reading and interpreting the defense is essential to any modern passing attack." At every level it has ever been implemented the Run and Shoot has been one of the most productive offenses in history. It has broken records everywhere it has been used, changed players' lives, made average players into all-stars, made losing teams into winning teams, scored over one hundred points in one game, and become the most feared weapon in the National Football League. Yet, at this time, only one National Football League team continues to employ the system, as opposed to the four that started the decade with it, and "run and shoot" has become one of the most hated phrases in the world of football. [Ed. Note: The Oilers stopped using the Run and Shoot after the 1993 season, the Lions after the 1994 season, and the Colts after the 1995 season. Along with some text near the end of the article, this implies that this essay was written in 1996, which would be the final season of the offense for the Falcons, and the NFL.] Once the misconceptions, myths, and negativity surrounding the Run and Shoot have been discarded, it will finally be able to take its place as one of the most extraordinary, balanced, and productive offenses in the history of the National Football League. Today, it cannot be associated with a one-faceted definition. It is, at its very essence, a combination of three things: a formation, a philosophy, and a system of eight plays. For the purposes of this paper, the Run and Shoot will be considered as the double slot formation popularized by Tiger Ellison, combined with his theory of route conversion based on a defender's actions, and the system of eight plays created by Mouse Davis. The ideas of the Run and Shoot were destined to take the N.F.L. by storm, yet it now it borders on extinction. The question now becomes why.

The first reason that the Run and Shoot has not continued to survive is due to a lack of knowledge. Because of the many sources that this offense stems from, there are many preconceived notions about it, mostly that it is a radical offense. Mouse Davis even comes to admit that appearances have hurt his product. "I know it looks like sandlot football, but in fact, it takes more discipline than any other offense. The Run and Shoot is not all that radical really. After all, there is only so much anyone can do with eleven padded men on a one hundred yard field." Kevin Gilbride, a Davis assistant who served as the offensive coordinator for the Houston Oilers concurs: "You get pretty defensive about the whole system and you don't want to be. But you keep seeing all of these myths and inaccuracies and it makes you that way. I don't think there's any valid criticism except that we haven't gone to the Super Bowl." In Davis' Run and Shoot, he used the concept of running a man across the formation in motion. This helped his team determine how it was being defended, and outflanked zone coverages or created mismatches in man coverage. When an offense puts three receivers to one side, it is referred to as a "trips" formation. A defense's reaction to trips was a large part of how the Run and Shoot would operate. If no reaction ensued, then the offense outnumbered the defense at the trips side. If the defense adjusted their coverage to the trips side, then they left the single receiver in one on one coverage with a whole half of the field to operate in. If they removed a player from the front seven, then they were leaving themselves at a disadvantage to play the running game. So the Run and Shoot is not all that radical, in fact, it can be considered conservative since it takes what the defense gives it and doesn't force the issue. Jim Kelly, who made his professional debut with the system, comments: "It's an either/or kind of thing. You can chip away, take what they give you, but in the back of your mind, you know that the capability for a big play is there on every snap. It's such a challenge to defenses because one mistake and you're in the end zone."

Seven prominent myths exist regarding the Run and Shoot, three of which have played large roles in preventing the offense from branching out. The first myth is that a formation of four wide receivers is great for moving out in the open field, but when it gets inside the red zone (opponent's twenty yard line), it lacks the muscle to score (most teams load up with three extra blockers for short situations). However, philosophical proof counters that having four wide receivers limits the personnel a defense can use, keeps fewer players up to stop the run, and plays into goal line situations because of its standard quick passing game. Statistics back up this notion, as from 1992 to 1994 Atlanta and Houston ranked third and fourth respectively in red zone efficiency and Detroit was #1 in 1990.

The second major myth is that since the Run and Shoot is primarily a passing offense, it does not have the power to sustain a powerful running game. This has been the biggest charge against the Run and Shoot, but it is also the biggest fallacy. In the 1950's, the theory of football was that the offensive players knew where they were going and the defense needed time to react. Therefore, if the offense executed properly, then by the time it took the defense to react to what was happening, the offense should be able to pick up an average of 3-1/3 yards every play. This would accomplish a first down every three plays and avoid having to punt. There were three major problems with this style of play. First, a team needed to pick up three and one third yards on each play to keep moving. However, if a team lost yardage, or gained a penalty, then they would have to pick up much more yardage and the theory of "reaction time" gains was not equipped to account for that kind of error. Second, if a team fell behind, gaining only three yards a play would take much more time than was available to put them in position to get back into the contest. Finally, and the most obvious reason that the reaction time theory could not work was that if a team's players are not big enough to push the other team's eleven out of the way, there is no way anybody could pick up three yards every play. It is thought that since the Run and Shoot has only one back and no tight ends that it cannot effectively run the football. However, the idea that the Run and Shoot is a "passing fool's" offense is extremely farfetched. In fact, many coaches claim that they had better running production in the Run and Shoot than in any other offense. In 1959, returning to a more conventional formation meant returning to more conventional football for Tiger Ellison, and his Run and Shoot Offense was more of a scheme to spread defenses out and use this spacing to execute a traditional running game. By placing four receivers near the line of scrimmage, it forced defenses to break up their traditional nine man fronts , which opened up room for his running game. His plan was to obtain nine of his men in a proximity to only six of the defense's. Thus, only one of his basic plays was a pass. Consequently, Ellison is not known as a great innovator in passing strategy, but his concepts marked a drastic paradigm shift turning football from a battle of attrition to a battle of movement. This is clearly seen as in a conventional offense, a team must be superior to move 17 bodies in a twenty yard area. The Run and Shoot causes a 30% reduction in mass as, "the field is stretched horizontally by formation, and vertically by speed." Also, since teams have to use more defensive backs to cover the wide receivers, a team's best players (the linebackers) are removed from the game. At the University of Houston in 1989, Chuck Wheatherspoon led the nation with a 9.6 yards per carry average, which is still an NCAA record. In the N.F.L., it has produced five different 1,000 yard rushers on three different teams. Consistent production with different personnel speaks volumes about the system in place. An opponent from the U.S.F.L., Jimmy Carr, commented, "I was misled. I was strictly concerned about the pass." Carr watched as Davis' team took advantage of what the defense gave them and ran for 208 yards. As Davis puts it, "The only way to keep us from running is to allow us to pass."

The final misconception regarding the Run and Shoot is that many believe that because the Lions and Oilers no longer use it, and because of its history of bad luck in the playoffs, that defenses have caught up to it. Consider this. The offense has been around since 1958 and remained virtually unchanged since Mouse Davis created the package. In over thirty years of existence, it has had a winning season in all but two, won a Heisman trophy, produced the N.F.L.'s leading rusher, and made it as far as the final four in the N.F.L. Although the Atlanta Falcons remain the sole team using the Run and Shoot, in the 1995 season, they won eleven games and qualified for the playoffs under second year head coach and former Run and Shoot quarterback June Jones. Even more impressive is that the Atlanta Falcons in '95 became the first team in the history of the N.F.L to have a 4,000 yard passer (Jeff George), a 1,000 yard rusher (Craig Heyward) and three 1,000 yard receivers (Eric Metcalf, Bert Emanuel, and Terrance Mathis). For an offense to have production like that hardly suggests that defenses have caught up with it. Another fact to consider is that one thing that Ellison's Run and Shoot did was force a defense into a basic predictable coverage by throwing to the split receivers when a defense refused to split out to cover them. Because of the limits this formation put on a defense, it was much easier to predict where defenders would line up, and therefore easy to single out one man and read his movements to determine where to go with the ball. Thus, a defense cannot "catch up" to this offense because the receivers will adapt on the run, as they've been trained to do, and find a weakness in any defense. Another factor to consider is that since the Run and Shoot is not something you can draw on paper, a defense can't possibly prepare for it. The end result is that for anyone to believe in this offense, it must be completely researched and understood. Former Los Angeles Rams coach John Robinson put it best when he said, "I just don't feel comfortable coaching something I know so little about."

Recalling that the Run and Shoot has been viewed as an undisciplined offense, one quickly comes to the second source of resistance to the Run and Shoot: The media's tendency to blow negative issues out of proportion. There are many problems in the world of sports, but the Run and Shoot has been cruelly associated with them. The main idea to consider is that people, not the system, are to blame for these problems. There are three main sources to these negative incidents, The University of Houston, the University of Maryland, and the Houston Oilers. More than any other man, John Jenkins probably has caused the most problems for the image of the Run and Shoot offense. Jenkins first caught on to the scheme when he was special teams coach for Jack Pardee's Houston Gamblers in 1984. When Mouse Davis moved to become the head coach of the Denver Gold in 1985, Jenkins took over the offense and did not miss a beat. Jenkins followed Pardee to the University of Houston where the Run and Shoot was immediately installed. From 1987 to 1990, the Cougars went 31-6-1 and produced a Heisman winner in Andre Ware. When Pardee moved on to the Houston Oilers in 1990 the whole show belonged to Jenkins. What followed was one of the most controversial displays of football production ever seen. Was this man a genius or a maniac? His team, still on probation from before he and Pardee had arrived, went 10-1 in 1990. His second quarterback, David Klingler, broke 33 NCAA records, including throwing for 716 yards in one game, yet he did not win the Heisman Trophy and Jenkins became one of the most hated men in college football. The reason: the manner in which he won games. Jenkins constantly ran up the score on his opponents, possibly the most unethical act to football coaches. By keeping his starters in the game and continuing to throw the football long after the game's outcome was decided, Jenkins embarrassed schools by ridiculous margins such as 82-28, 95-21, 84-21, and 69-0. His quarterback once threw for eleven touchdown passes in a game against division 1- AA Eastern Washington. The scores were not the worst part. He made no attempt to ever apologize for his actions, and the manner in which he conducted himself made him unloved as well. He refused to share the secrets of his offense with high school coaches, prohibited others from watching his practices, and shredded his offensive play books after his players had memorized them . As he so lightly put it, "Do I.B.M. and Xerox share their policies so that some competitor can come in and kick their butts?" One rival coach put it best when he stated, "We survive in the coaching business by helping one another. Jenkins has shown an inability to do this. Everyone resents a guy who thinks he invented the game." Jenkins quickly was run out of town, his resignation coming after his record fell to 4-7 in back to back seasons and following allegations that he had violated NCAA rules for exceeding practice time limits and making payments to recruits. Jenkin's blatant abuse of power left a bitter taste in the mouths of most of the football world. He provided an example of how powerful this system could be, but also how it could be abused.

Two separate incidents from the University of Maryland gave the Run and Shoot a bad image, one on the field, and one off. On the field, the Maryland offense was producing unheard of numbers, averaging over 45 points a game. Unfortunately, Coach Mark Duffner did not have the talent to put up a great defense. In fact, his defense was considered the worst in the nation. Because of this futility, giving up 53.8 points a game and over 606 yards, the myth was created that Run and Shoot was thought to make your defense weaker because of the amount of practice time needed to work on the offense, plus the fact that the defense never gets to work against a tight end or fullback because Run and Shoot teams do not carry such players. The second incident involved quarterback Scott Milanovich, owner of 11 school records, who, in 1994, was suspended for 11 games for gambling . This incident only added to the attacks being made on the soundness of the Run and Shoot and was one of the factors contributing to Duffner's dismissal in 1996.

As the team that ran the Run and Shoot for more years (7) than anyone else, the Houston Oilers were constantly in the spotlight. Houston holds the record for most consecutive playoff appearances, qualifying every year they employed the Run and Shoot, from 1987-1993. In 1990, quarterback Warren Moon threw for 527 yards in one game, the second most in N.F.L. history. Throughout those years, Houston led the league in most categories of offensive production. Yet, 1994 found them firing Offensive Coordinator Kevin Gilbride, Head Coach Jack Pardee, and axing the Run and Shoot. The reasons why are somewhat confounding. In December of 1992, the Oilers had destroyed the Buffalo Bills in the last regular season game. The next week, they were paired up with the Bills again in the first round of the N.F.L. playoffs. In the first half, the Oilers picked up right where they left off, with Moon completing 19 out of 22 attempts for 218 yards and four touchdowns in the first half and leading 28-3. The score was stretched to 35-3 in the third quarter. Houston's subsequent collapse was the greatest comeback in N.F.L. history, seen by millions of viewers on national television. Buffalo came back to win the game in overtime, 41-38, costing two defensive coaches their jobs, and the Oilers a chance at a possible Super Bowl. Two years later, after Pardee was fired, it was written, "The perception that Pardee has failed in Houston cannot be blamed on his use of the Run and Shoot. It can be stated in one word: Buffalo." What that means is the Buffalo game marked a turning point, for it was this utter humiliation, which forced owner Bud Adams to seriously consider making changes. The Run and Shoot administration survived that fiasco, as Gilbride's offense could hardly be blamed for the debacle. However, Adams hired Buddy Ryan to serve as defensive coordinator, which was like lighting a match in a powder keg. No one had been more outspoken about the Run and Shoot than Buddy Ryan. He constantly referred to it as the "chuck and duck" and once said that Kevin Gilbride, "should be selling insurance." Houston started the '93 season 1-4, but won its final eleven games to finish 12-4 and became the favorite to win the Super Bowl. However, the incident that everyone would point to in Houston was Buddy Ryan punching Kevin Gilbride on the sideline of a nationally televised game. The Oilers continued their bad playoff luck by falling to the Kansas City Chiefs 28-20. Their failure in seven years to make it past the divisional round of the playoffs caused owner Bud Adams to say goodbye to the Run and Shoot. Yet it seemed that everyone could see that it was the media that was causing Adams to act this way and not sound football logic. "I've got to think Houston is three quarters crazy, " said Mouse Davis, "With what they've accomplished why would they want to do that? You'd think a lot of it was reacting to the media heat without a lot of thought." Quarterback Warren Moon, who was on his way out as well concurred. "I think they're doing it because of public outcry for change." Even more impressive is the fact that opposing players defended the usage of the Run and Shoot. Kansas City Chief All-Pro Linebacker Derrick Thomas remarked "I think it 's a bad rap that the Run and Shoot can't win the big one. I've seen them beat everyone on their schedule. Look at the numbers they've posted. They've won more games than a lot of "conservative" offenses. I just don't see how you can change something that works." All-Pro Cornerback Rod Woodson of the Pittsburgh Steelers, who has to face the offense twice a year said, "Tell the owner thank you, tell the front office thank you. The Run and Shoot got the Oilers where they are. I think defenses all over the league are going to be very relieved." Thus the media had claimed one more victim, but this one was the torch carrier that had the future of the Run and Shoot offense riding on its fate. Half the rap against the Run and Shoot was the result of off the field incidents that had nothing to do with the offense, but distracted from the real picture.

As one will recall, Mouse Davis took the Ellison model and created an eight play package. Using the discipline Mouse Davis instilled into the package, the offense began to take off nationally. Scores of 105-0, 93-7, and 75-0, became common as Davis' system continually befuddled high school coaches and then college coaches during his move to Portland State University. The aspect that the Run and Shoot was beginning to bring to the college ranks was that of calculated strategy. "It was so scientific," stated Paul Costanzo, Mouse's first Run and Shoot Quarterback, now an English professor at Carnegie Mellon, "It turns smash mouth football into tennis," referring to a game in which a ball has to be placed into an area away from the opponent. Calculating technicians were not the only ones attracted to the Run and Shoot. In 1975, June Jones quarterbacked for Davis and went from an unwanted transfer to a quarterback who would go on to break the NCAA division II single season passing record and be drafted by the Atlanta Falcons. He admits readily, that, without Mouse Davis and the Run and Shoot, he would never have played a down in the N.F.L. In 1977 Mouse took Neil Lomax, a player that no school had recruited, and he would go on to break 20 NCAA passing records, his team averaging 49 points a game, and be drafted by the St. Louis Cardinals. In 1982, Davis found himself as offensive coordinator of the Canadian Football League's Toronto Argonauts, and in one year took them from a last place team to the Grey Cup (the C.F.L's championship game). Nineteen eighty four finally found this man in American professional football, as offensive coordinator under Jack Pardee for the U.S.F.L's Houston Gamblers. Here, he may have enjoyed his greatest success. With future NFL stars such as Jim Kelly, Ricky Sanders, Clarence Verdin, Gerald McNeil, and Richard Johnson, the Gamblers went on to post numbers that professional football had never seen before. Jim Kelly became the first professional passer to amass 5,000 yards passing, and Richard Johnson and Ricky Sanders became the first teammates to surpass 1,000 yards receiving in the same season. After a year hiatus, following the disbanding of the U.S.F.L., Davis was hired by Wayne Fontes of the Detroit Lions to be his offensive coordinator. By 1991, people in contact with Mouse Davis had spread his offense to dozens of colleges, could boast a Heisman Trophy winner (University of Houston's Andre Ware), and found themselves on the staffs of three N.F.L playoff teams, the Atlanta Falcons, the Houston Oilers, and the aforementioned Lions. How could this production be ignored?

Wherever the Run and Shoot has gone, it has been seen as a renegade offense. An offense that allowed players who weren't good enough to play the game to excel. In Ellison's book, he bases his theory on the fact that an average passer with average receivers can move the football if they all follow a few simple rules. Mouse Davis, the creator once said, "Kids can play in our offense who can't play anywhere else." At Portland State, Jones relates that: "We excelled with major college rejects playing against schools carrying 90 scholarships. We were undersized, we were out-manned, and week after week we would physically get killed. Yet they would win by scores of 93-7, 105-0, and 75-0. This idea also existed at the University of Houston, with Jack Pardee laying out his mission statement: "It would have taken the height of egotism to think the University of Houston would settle for a lot players of that Texas and Texas A&M didn't want, run the same plays, use the the same system and beat them. So, our approach was to go after a different kind of player, teach them a different kind of system, and teach them well." This underdog image was especially evident at the professional level. The only way a team was going to use the Run and Shoot was because it had no where to go but up. "For an N.F.L. team to try the Run and Shoot, it takes a team like Detroit. It needs fans, it needs points, and hasn't been winning."

Because of the image it had portrayed at these major levels, established N.F.L. teams refused to try it. If it is an offense for underdogs and teams that aren't good enough to play the game the real way, why should they use it? It must have seemed like the Run and Shoot was like studying for a test. The established teams felt that if they didn't have to study, why bother. The weaker teams, needing any chance they could get to compete, jumped at the chance. What the Run and Shoot needed was for an established team to say, "We don't have to do this, but we may as well learn it in case we need it." All evidence seems to suggest that if an established power had put aside its stubborn, conservative, traditional outlook, and tried the offense, the Run and Shoot may still have a chance. The Houston Oilers in 1993 were the closest to making this happen, winning 11 games in a row and making a run to the Super Bowl, but two things stood in the way of establishing credibility for the Run and Shoot. First, their rise had occurred entirely since their employment of the Run and Shoot, so even though they had many talented players on both sides of the ball, the media still saw the system as the sole reason for their success. Second, owner Bud Adams showed little patience as he dismantled his best team in reaction to his teams seventh year of playoff frustrations.

The Run and Shoot is one of the most misunderstood topics in the history of the game of American football. However, the myths, media attacks, and image that have continually degraded its existence are obviously unjust and refutable. The Run and Shoot is a solid, well balanced offense that can bring underdogs up to the next level, but with established players can be unstoppable. It is truly a crime that such a potent weapon is used so sparingly in the world of football today. The only consoling fact is that almost every team incorporates part of the Run and Shoot philosophy into their packages, a tribute to the influence that Davis and his system have had on the game. However, there are many coaches out there with new and invigorating ideas that deserve a chance to show their stuff. Football, like life, is a competitive game. However, it has been proven that there are ways to succeed without being the biggest, fastest, or strongest. With the league's opposition to the Run and Shoot, the N.F.L. is sticking to its conservative guns, sending the message that "might makes right," and spectacles like the Run and Shoot will not exist because, "that's not the way things have been done in the past." One day the train will come to town, and educated, ethical, credible coaches will turn it around, giving this weapon one more chance.

Originally posted on http://www.geocities.com/dmaly82/mellor1.htm

Great article, I like how you broke down the the misconceptions as well.

ReplyDeleteI'm thinking of picking up Glen's Book the offense of the future

Well we really like to visit this site, many useful information we can get here. learn about doctor gardening

ReplyDelete