As an assistant coach, my job is to help the head coach implement his vision, so none of the following is intended as criticism. I also fully understand that running the wishbone with the younger kids gets them familiar with the formation so they are ready to run the option from it when they get older. But if the goal were just to have a team of young kids run the ball with power and misdirection, there are simpler ways to do it, like this:

The Rocket Sweep

First, I would switch from double-tight wishbone to flexbone for two reasons, neither of which has anything to do with passing. For one, split end is a place where some of the lesser talented kids can get snaps. By that I don't mean "hide" a kid out there and let him get his minimum number of plays while we run the opposite way. I mean give kids a meaningful task they can accomplish, even if they are lacking in size or speed. A split end can block a corner any way he wants to go, and the back should be able to read and cut off that block, making everyone a part of a successful play. The second reason is to put the halfbacks (now slotbacks) in better position to block on the sweep and wedge plays that are staples of youth offense. If a defensive coordinator sees my four 10-year old receivers and decides he needs to back up his safeties, bonus. I wouldn't.

I would also choose a small number of plays that work together to constrain the defense. In what Ted Seay calls "unity of apparent intent," a series of plays that complement each other puts stress on the defense in various ways and locations while all maintaining a similar appearance, so the defense can't "play the play." Ideally, the plays in this series also put the defensive players "in conflict," so their ideal technique against one play is a liability against another. A fundamental aspect of the Delaware Wing-T offense, this ensures there is a ready-made response to any defensive adjustment.

The Base Play: Sweep

Most of the time, youth football offense comes down to getting your fastest player on the edge with the ball. This is true of football offense in general, but at the youth level each team's fastest two or three players are often so much faster than everyone else on the field that it overwhelms all other strategic considerations. High school teams might talk about running the "sweep till they weep," but at the youth level you really can run the sweep all day (and you really do have to watch out for weeping). There isn't a better way to get a fast player on the edge than the rocket sweep, which is a sort of deranged nephew of the jet sweep. In the jet the motion back comes flat down the line of scrimmage before taking the handoff at a full sprint, bellying back slightly to get around the edge, then running a wheel path through the hashes, the numbers, and up the sideline. As long as the handoff timing is good and the sweeper runs full speed, there is no need to block anyone inside of the C gap:

The rocket does the jet one better. The sweeper goes in deeper motion, through the heels of the fullback, and takes a toss from the quarterback instead of a handoff. Rocket motion takes away some of the ways that a player in jet motion can be used as a receiver or blocker, but it makes the already effective jet sweep even more devastating. Done correctly, there is no need to block anyone inside the D gap, meaning the entire offensive line is free to either pull and lead or rip through to the second level:

To stop the rocket, the defense has to compensate numerically on the playside for the introduction of the motion sweeper coming across the formation. How they compensate determines which complementary plays will be most effective. The game here is to create, with as few offensive plays as possible, a complete offensive series to take advantage of as many possible defensive adjustments as possible. I think that for most youth teams, about five plays is a good (admittedly arbitrary) number of plays for the core offense. Five plays can form a complete series of complementary plays without burdening a young mind with too much memorization. Extra plays can be added to the core of six, but should be few and focused on a clear objective.

For the fullback, running the trap requires some practice and trust with the guard, who will be crossing his face just before he hits the hole. He should stay low, hiding from the defense and giving them nothing to hit but shoulders and knees, while still keeping his head up for vision and safety. He will cover the ball with both hands, but will be ready to put one hand down to keep his balance if he takes a hit after clearing the first level.

The Trap

If the defense compensates for the sweeper motion by sliding the undercoverage over:

or by rotating the secondary up:

then the trap to the fullback is a fast hitting run up the middle taking advantage of defenders who have vacated the middle and/or started moving toward the motion sweep. Although the trap can be run toward or away from the sweep motion, there are two good reasons to "trap back," running away from the motion direction:

- With the exception of the trapping guard, all other offensive linemen are blocking in the direction the defenders are drawn to by the sweep fake.

- Sending the fullback to the backside sets him up to be a more immediate receiver on the bootleg.

For the fullback, running the trap requires some practice and trust with the guard, who will be crossing his face just before he hits the hole. He should stay low, hiding from the defense and giving them nothing to hit but shoulders and knees, while still keeping his head up for vision and safety. He will cover the ball with both hands, but will be ready to put one hand down to keep his balance if he takes a hit after clearing the first level.

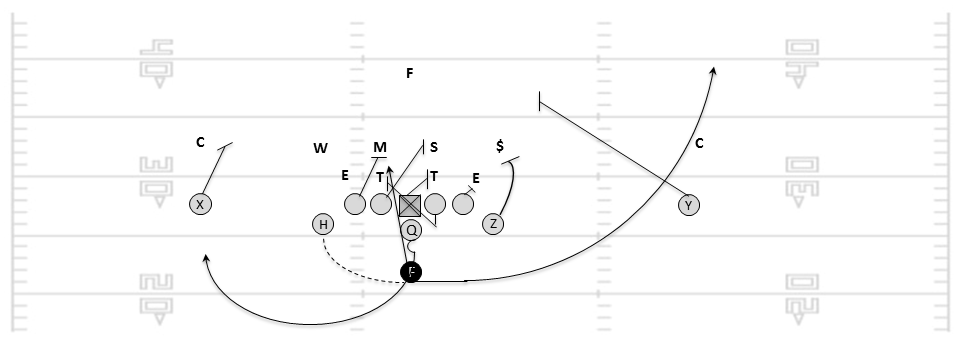

The Bootleg

If the defense responds to the motion by sending the player covering the motion man across the formation, it has declared man coverage and also removed one of the players most used to setting the edge against a wide run. (At higher levels of football, teams can run a player across the formation and still play zone, but it's relatively uncommon at all levels.) The crossing action of the bootleg routes makes them hard to cover man to man, while also getting blockers into position if the quarterback decides to keep it and run:

After making great fakes on the fake pitch and fake handoff, the quarterback should get depth and roll out while looking for the split end on the corner route. If the split end can't get deeper and wider than the cornerback, and the fullback can't get wide of his defender in the flat, the quarterback should keep and run inside the block of the fullback, an outcome that will probably happen half the time or more. In addition to taking advantage of overreaction to the sweep motion, the bootleg also punishes a backside defensive end who crashes down the line anticipating the trap. The backside defensive tackle can be tempted to shoot through to get a hit on the quarterback, but that opens him up to being trapped.

After making great fakes on the fake pitch and fake handoff, the quarterback should get depth and roll out while looking for the split end on the corner route. If the split end can't get deeper and wider than the cornerback, and the fullback can't get wide of his defender in the flat, the quarterback should keep and run inside the block of the fullback, an outcome that will probably happen half the time or more. In addition to taking advantage of overreaction to the sweep motion, the bootleg also punishes a backside defensive end who crashes down the line anticipating the trap. The backside defensive tackle can be tempted to shoot through to get a hit on the quarterback, but that opens him up to being trapped.

The Wedge

The combination of rocket sweep, trap, and bootleg creates a complete series (the Wing-T buck sweep series, in fact) to constrain the defense. Additional plays should be added for a particular purpose, with the goal of having as few as necessary. The Wedge play superficially resembles a quarterback sneak, but it is much more than that - it's a consistent ground gainer that can easily break for long yardage. It is the ultimate team play, as the force of seven players is concentrated on one spot, and it is also the ultimate youth play, as it is simple to teach but hard to stop without great discipline, a quality... typically lacking in most young children. Furthermore, it is a great fit for the double slot formation used here, as the wingbacks are already in excellent wedge position, the line splits are already tight to shorten the corner for the sweep, and the defense is already stretched laterally by the wide split ends and the threat of the sweep.

Instead of blocking a defender, linemen running the wedge block into each other: the guards step inside and block into each side of the center's back, the tackles step halfway behind the guards and push them, and the wingbacks do the same for the tackles, forming a tight triangular enclosure around the quarterback. It is illegal (though almost never called) for a blocker to assist a runner with a push, but completely legal for one blocker to assist another blocker in this way. Is is, however, illegal for blockers to interlock arms or hold each other, so they must resist any temptation to grab when they push each other. In fact, they should leave their inside arm folded inward like a flipper rather than putting a hand on their teammate's back, because to a referee a hand on the back is indistinguishable from a grab. The QB should pause for a beat to let the wedge form around him, then fit tightly inside and ride the wave forward as far as possible. After several yards, the wedge will begin to break down, at which point the QB has to pick the right moment and spot to break out of the wedge and run for open field. The fullback should turn and block any defender looping around the wedge to catch the QB from behind.

Three things can stop the wedge: penetration by the defensive line (call the trap), overwhelming numbers (call the sweep) and players looping around to catch the runner from behind. If those can be controlled, the wedge should go. As Don Markham has noted, the quarterback wedge, particularly on a silent count, is almost an offense unto itself. This play can also be called with or without sweep motion, making it too good of a play not to include in the playbook.

Instead of blocking a defender, linemen running the wedge block into each other: the guards step inside and block into each side of the center's back, the tackles step halfway behind the guards and push them, and the wingbacks do the same for the tackles, forming a tight triangular enclosure around the quarterback. It is illegal (though almost never called) for a blocker to assist a runner with a push, but completely legal for one blocker to assist another blocker in this way. Is is, however, illegal for blockers to interlock arms or hold each other, so they must resist any temptation to grab when they push each other. In fact, they should leave their inside arm folded inward like a flipper rather than putting a hand on their teammate's back, because to a referee a hand on the back is indistinguishable from a grab. The QB should pause for a beat to let the wedge form around him, then fit tightly inside and ride the wave forward as far as possible. After several yards, the wedge will begin to break down, at which point the QB has to pick the right moment and spot to break out of the wedge and run for open field. The fullback should turn and block any defender looping around the wedge to catch the QB from behind.

Three things can stop the wedge: penetration by the defensive line (call the trap), overwhelming numbers (call the sweep) and players looping around to catch the runner from behind. If those can be controlled, the wedge should go. As Don Markham has noted, the quarterback wedge, particularly on a silent count, is almost an offense unto itself. This play can also be called with or without sweep motion, making it too good of a play not to include in the playbook.

The Reverse

There are several possibilities for the final play in the playbook - a quick kick, dropback pass, or off-tackle power would make sense. But a misdirection run fits best with the horizontal sweeping action. An inside counter to the slotback sounds tempting, but I'll go with a split end reverse as a simple way to take advantage of overpursuit. As an added bonus, this gives another way to get the ball to those hardworking blocking split ends.

There's also the wing back counter. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oKIGLvpq9vw

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteHey coach what type of line splits would you suggest for 5th-7th graders?

ReplyDeleteDo you tighten splits on wedge play or stay foot to foot for all plays?

ran this in high-school with almost no success. but find myself gravitating towards in for my first year coaching 4th graders.

ReplyDelete